Breakpoints in Burp

No, this is not a story about the Canadian Thanksgiving long weekend, it's about web application testing. I recently had a web application to assess, and I used Burp Suite Pro as part of that project. Burp is one of my favourite tools to aim at a website, it does a lot of the up-front "test everything" grunt work for you so you can then focus on the details that are most important.

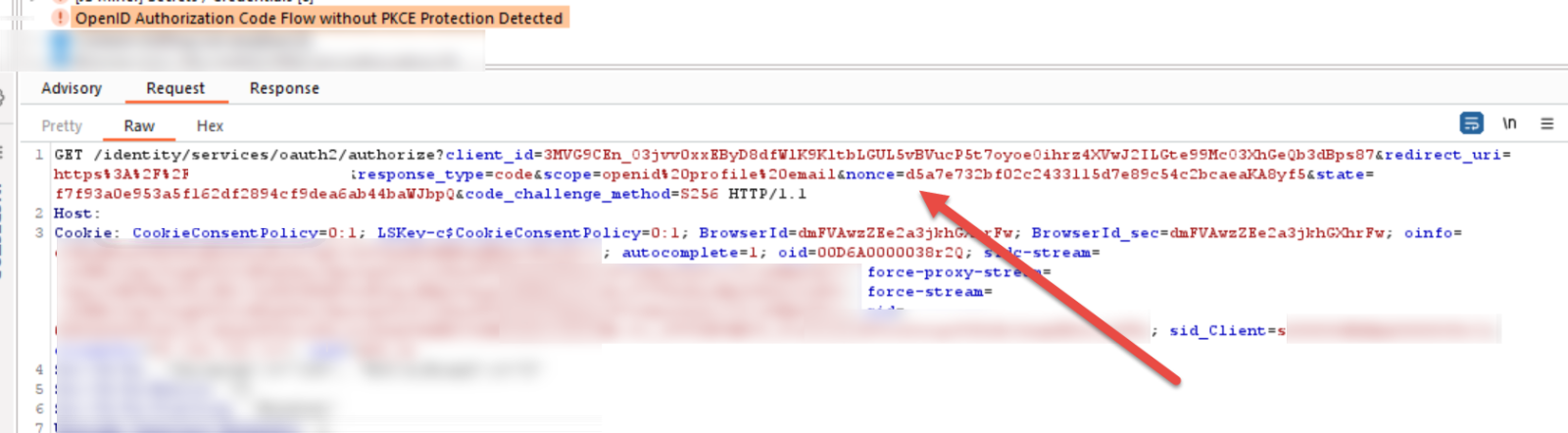

One of the findings was "OpenID Authorization Code Flow without PKCE Protection Detected", coupled with "OpenID Authorization code Flow without Nonce Parameter". This story isn't about these issues specifically, but how to deal with complex web app code flow issues in Burp.

We're all familiar with Breakpoints - in their simplest terms, when you write code and put in random lines that print out "Code got to here, variable $something = some value", that's a breakpoint. If you write complied code or assembly, breakpoints can mean something more complex. In Burp, by default "proxy intercept" is on, which means that for every request and response the app will intercept that data and present it to you for inspection or modification. You can see how in a complex web app you don't want that for EVERY page. What I needed was:

- Turn off proxy intercept so that I don't have to click "OK OK OK" a dozen times for each page load

- However, turn the proxy intercept back on when I get to a specific page, see a particular variable or some combination of "stop here, this is the spot" set of conditions.

- At that point, I'm at the proxy intercept screen and can either single-step from there, or change variables to see what happens as the code progresses along.

Does that sound complicated? Maybe so, but it's simpler once we look at it for real.

First, this is the raw "finding" that Burp displays. Note the "nonce=" parameter - that's what we're looking for in our breakpoint.

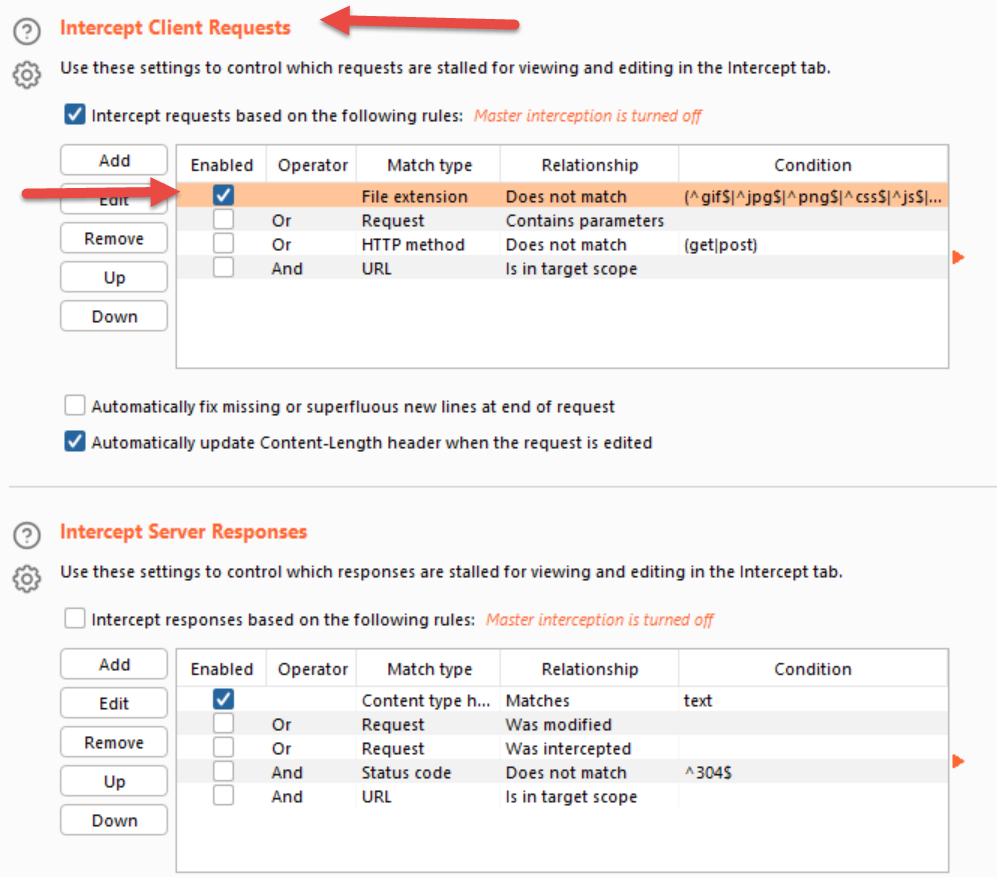

Next, in Burp navigate to the the Proxy / Options page, and edit "Intercept Client Requests" - this screenshot shows the default settings:

Note in the lower half of the screenshot above that you can also set breakpoints on the info that gets sent from the server to the client. The default client-side intercept settings shown here are: "intercept everything except for this default list of file extensions". On the server side, the intercept settings are "intercept everything that looks like text"

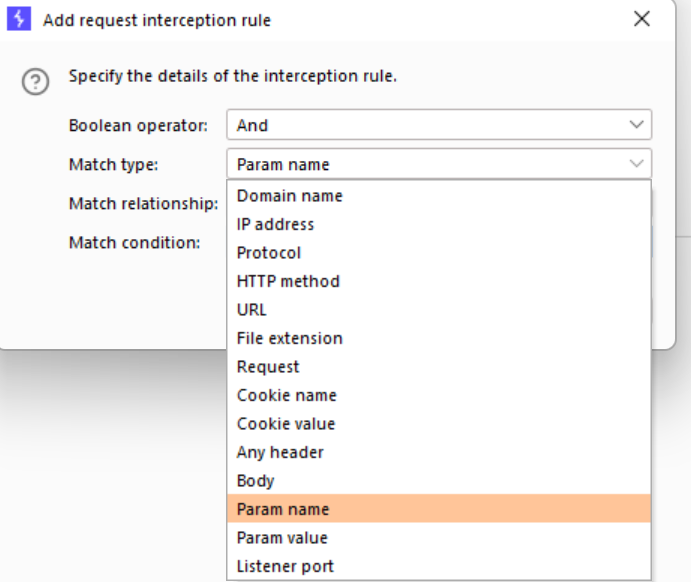

We'll disable those default settings and add our own - we want the intercept to turn on ONLY when the "nonce" parameter makes an appearance. Note how many options you can pick to combine together (with ANDs and ORs) to make up your condition:

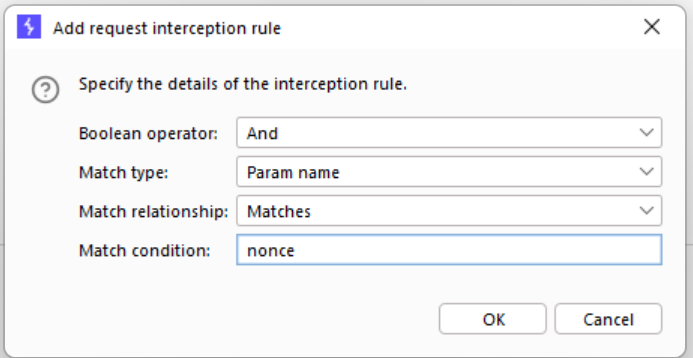

In our case it's pretty simple - stop when you see the "nonce" parameter:

Now, with that set and intercept enabled, I went back to the login page and logged in, answered the MFA prompt and all the things. When the "nonce" parameter appears in the request or response - BOOM, things stop and I'm looking at the request.

If you are looking to save time in Burp, this is a great way to do exactly that!

What happened? It turns out that I could edit the nonce value to anything (including zero or deleting it altogether) and the login would still succeed. Even if I changed it several screens in, or in the server response the login would still succeed. It turns out that the provider didn't use the nonce.

The nonce is an important piece of the authentication puzzle - it's what associates the client session with the ID token and is used to prevent replay attacks. Of the 3 options for OpenID + OAuth, two of them require the nonce (Implicit and Hybrid) and the nonce value is not required but is still recommended for the third option (Auth Code). If you are using PKCE (for instance for handing the code flow back to a mobile app), if you don't specify a nonce value, it's supposed to use the value of "state" for the nonce to at least force a value. Long story short, the finding was a real thing - go go gadget burp! (wait, that still doesn't sound right ...)

Got a fun situation where you used breakpoints in a web test? By all means, share using our comment form!

===============

Rob VandenBrink

rob@coherentsecurity.com

Who put the "Dark" in DarkVNC?

Introduction

VNC is an acronym for Virtual Network Computing. It is a way of controlling a computer remotely from another computer. VNC is similar to a Remote Access Tool (RAT). But unlike a RAT, VNC is a cross-platform screen sharing system that allows full keyboard and visual control, as if you were physically present at the remote host.

VNC-based malware has been part of our threat landscape for a long time. In recent years, some VNC-based malware has been referred to as DarkVNC or HiddenVNC.

During the past year or so, I've referred to any VNC activity I've run across as DarkVNC. But not all VNC traffic is necessarily DarkVNC, so let's figure out who put the "Dark" in DarkVNC. To answer that question, this diary reviews VNC-based malware samples and activity since 2013.

VirusTotal's first DarkVNC sample

VirusTotal's sandbox C2AE will flag certain samples with tags indicating various malware families. One such flag is RAT (DarkVNC). This is a searchable flag for people with a VirusTotal Intelligence subscription. The first DarkVNC-flagged sample was submitted to VirusTotal on 2013-04-03. This sample shows a creation date of 2012-12-24. The SHA256 hash is:

I found my first DarkVNC sample in 2017 as one of the payloads from a Terror Exploit Kit (EK) infection. That DarkVNC sample generated traffic to 85.17.29.102:443 and triggered an alert for ETPRO TROJAN W32/DarkVNC Checkin. This activity was referenced in a ReaQta blog in 2017 about DarkVNC that is currently available through archive.org.

I didn't see DarkVNC again until mid-2021, when I started discovering newer examples of VNC activity. One VNC-based malware sample triggered an alert for ETPRO MALWARE VNCStartServer USR Variant CnC Beacon on 172.241.27.226:443. The associated Twitter thread reveals that sample is possibly a HiddenVNC variant of DarkVNC. Or HiddenVNC is likely another term for samples that others have identified as DarkVNC.

Current example of VNC-based malware traffic

What does VNC-based malware traffic look like? In recent months, I've occasionally found VNC traffic as follow-up activity from IcedID and Qakbot infections. For Qakbot, follow-up VNC activity has been on 78.31.67.7:443 since as early as June 2022. When Qakbot's VNC is active, we see two TCP streams using the same IP and port, both running at the same time.

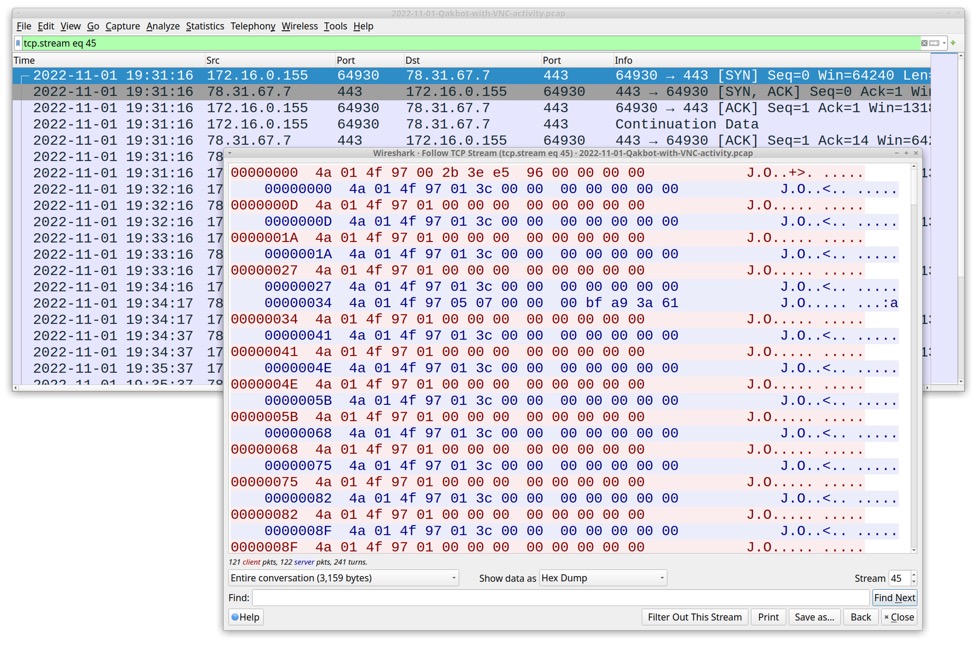

The first TCP stream appears to be a VNC beacon that sends mostly the same sequence of 13 bytes from the infected host. The infected host then receives mostly the same 13 bytes from the VNC server. This traffic keeps repeating as long as the VNC session is active. See the below image for details.

Shown above: TCP stream of the VNC beacon activity shown in Wireshark.

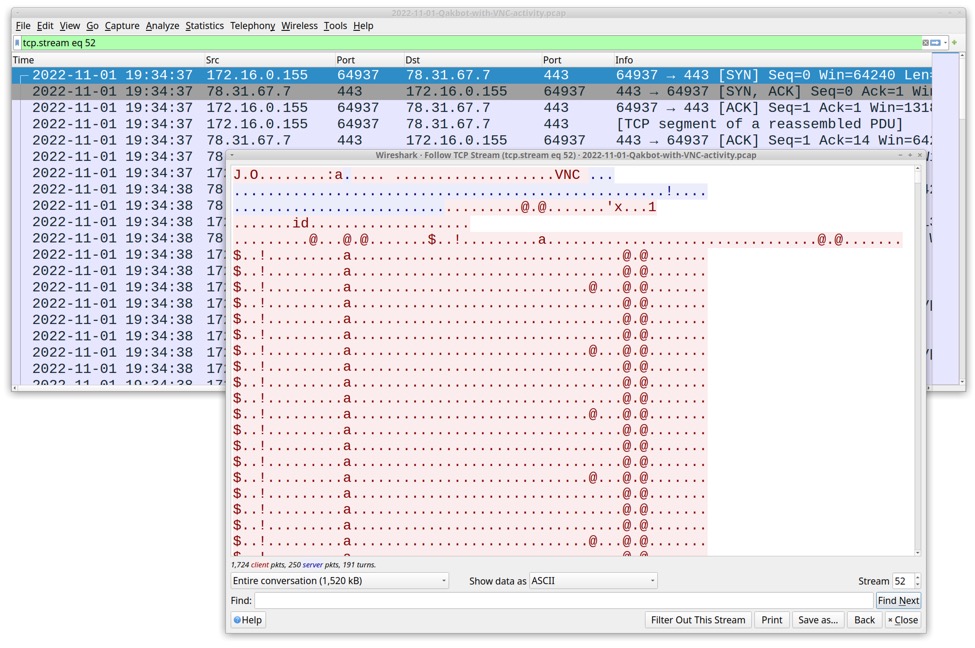

The second TCP stream for VNC traffic contains much more data, most of it encoded or encrypted, likely related to the screen sharing and keyboard/mouse control used in VNC activity. This traffic is easily identified by the ASCII characters VNC somewhere within the first hundred bytes of the TCP stream. The initial traffic contains a repeating pattern of bytes that provide a distinct visual when viewing the TCP stream. See the image below for details.

Shown above: The second TCP stream for VNC traffic that contains much more data than the first stream.

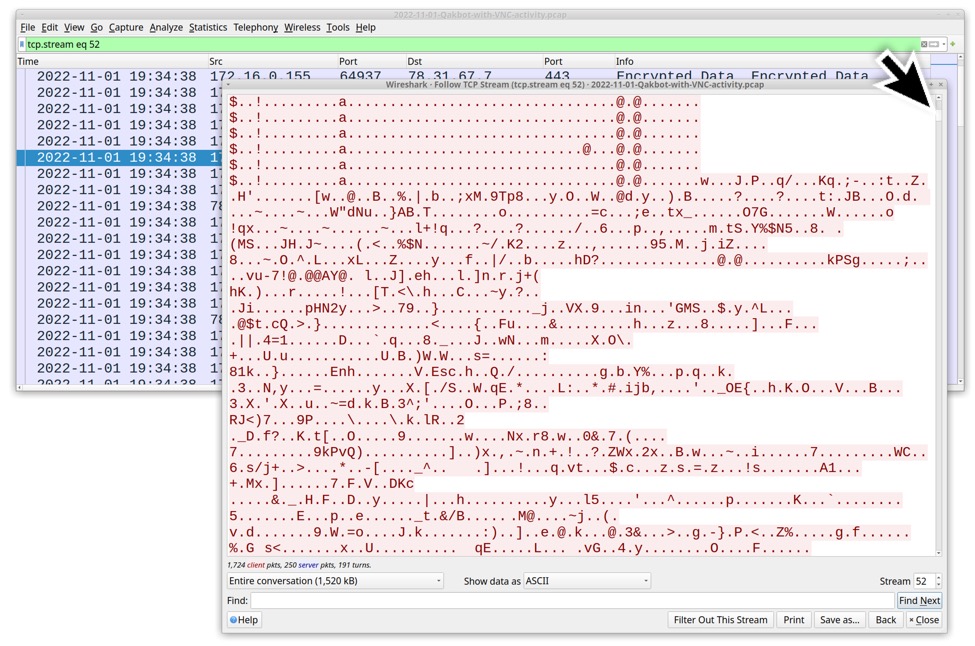

Later in the TCP stream, we start seeing data possibly related to the screen sharing and keyboard/mouse control for VNC traffic. See the image below for details.

Shown above: Data in the second TCP stream possibly related to VNC screen sharing and keyboard/mouse control.

Of note, VNC activity from Qakbot infections prior to June 2022 has three TCP streams (two beaconing and one data stream) that looked much more like traffic from older samples identified as DarkVNC. Here is a previous diary from March 2022 featuring a Qakbot infection with VNC activity that more closely matches what many think of as DarkVNC or HiddenVNC. This includes strings with the infected hostname and Windows user account name in the two beaconing TCP streams.

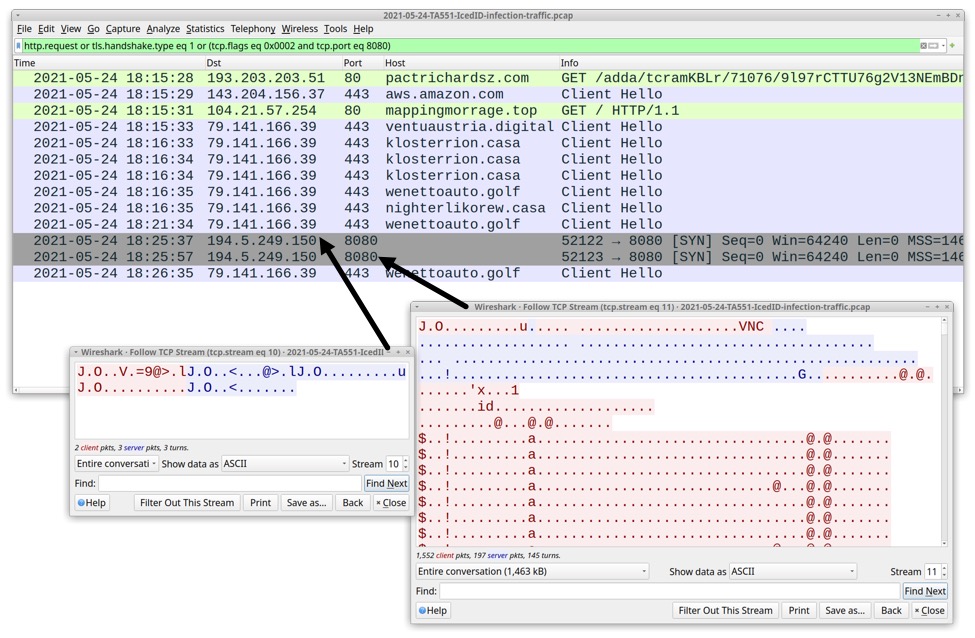

However, in recent months, VNC activity from Qakbot infections match patterns we've seen for VNC activity from IcedID infections. Below is an example of IcedID with VNC traffic from May 2021. It looks remarkably similar to VNC from IcedID and Qakbot today.

Shown above: VNC traffic from an IcedID infection on 2021-05-24 similar to VNC from a Qakbot infection on 2022-11-01.

Previous examples of follow-up VNC activity from other malware

Below is a list of blog posts where pcaps are available with VNC traffic from BazarLoader, IcedID, Qakbot, and Trickbot infections since May 2021. Some of these I didn't realize had VNC traffic at the time. I originally called most of this activity DarkVNC, but that's not exactly correct. According to Netresec, VNC traffic typically seen with IcedID is part of the IcedID BackConnect protocol. Since June 2022, I'm seeing the same sort of VNC traffic from Qakbot infections, so I wonder if Qakbot has adopted parts of the same protocol. I also saw similar VNC traffic from BazarLoader in November 2021.

Click on links in the dates to access my blog pages for the associated pcaps.

- 2021-05-24: TA551 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 194.5.249.150:8080

- 2021-06-02: TA551 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 38.135.122.194:8080

- 2021-06-30: TA551 Trickbot with DarkVNC on 172.241.27.226:443

- 2021-11-05: TA551 BazarLoader with VNC on 87.120.8.190:9090

- 2021-12-10: TA551 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 88.119.161.76:8080

- 2021-12-13: TA551 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 88.119.161.88:8080

- 2022-01-12: IcedID from email --> link --> XLL file, with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 45.147.228.197:8080

- 2022-03-15: obama166 Qakbot with VNC traffic on 45.153.241.142:443

- 2022-04-14: aa Qakbot with VNC traffic on 45.153.241.142:443

- 2022-04-19: aa Qakbot with VNC traffic on 45.153.241.142:443

- 2022-05-23: IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 88.119.161.76:8080

- 2022-06-07: obama186 Qakbot with VNC traffic on 78.31.67.7:443

- 2022-06-21: aa Qakbot with VNC traffic on 78.31.67.7:443

- 2022-06-27: obama194 Qakbot with VNC traffic on 78.31.67.7:443

- 2022-06-28: TA578 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 91.238.50.80:8080

- 2022-07-06: TA578 IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 188.40.246.37:8080

- 2022-07-21: IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 212.114.52.91:8080

- 2022-07-26: IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 135.181.175.108:8080

- 2022-10-04: IcedID using IcedID BackConnect C2 51.89.201.236:443 without VNC

- 2022-10-31: IcedID with VNC over IcedID BackConnect C2 on 137.74.104.108:8080

Conclusion

Who put the "Dark" in DarkVNC? I don't know. Perhaps it's based on how the malware was advertised by criminals in underground forums, but that's merely a guess on my part.

VNC-based malware traffic patterns have changed since I first saw it, so I'll stop calling it DarkVNC. From now on, I'll refer to the activity as VNC or malicious VNC.

---

Brad Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

Comments